Is slime conscious?!?

A not so elegant but quite remarkable example one could present about cellular intelligence is the abilities of the ‘Physarum polycephalum’, a large amoeba-like slime mold ‘plasmodium’–that is, a fungal cytoplasm containing several nuclei but enclosed in a single membrane–that can be considered as a single giant cell. It is a slimy creature reminiscent of the ‘The Blob’, the alien amoeboid being that appeared in the popular sci-fi and horror film in 1958. It changes its shape as it crawls in search of food as a yellow network of tube-like structures that grow a few centimeters per hour and whose movement can be captured via time-lapse recordings.

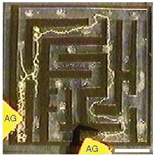

This slime mold has several skills and behavioral patterns that could be labeled as ‘proto-intelligent’ and that one would hardly associate with such a primitive creature. For example, it can find the minimum length between two points in a labyrinth. When P. polycephalum is grown in a maze with nutrients at two spots, it first invades the entire labyrinth until it finds its food and then retracts its pseudopods, leaving intact only those corresponding to the shortest path connecting the two food sources (see link).

Further research showed that P. polycephalum can minimize the network path and complexity between multiple food sources. Conditioned behavior was shown as well. When this plasmodium is exposed to a sequence of three dryers and cooler life-threatening conditions at constant time intervals, it reduces its speed of growth or stops entirely for a while before starting to grow again after each pulse. Once conditioned, it learns to anticipate the arrival of the second and third shock even if one administers only the first pulse and leaves out the other ones. This and other research shows that this slime mold can memorize and learn to anticipate periodic events.

P. polycephalum is also able to adjust to unfavorable circumstances. If one forces it to cross an agar bridge with caffeine or quinine at toxic but not killing concentrations, it first slows down but, after repeated attempts, nevertheless crosses the bridge at the same speed in the absence of the irritant substances. It was believed that this was something only neural networks could do: learning to ignore negative repeated stimuli. That is, a learning process of habituation took place.

Slime molds also remember food location having memory about the environment. Research indicates that this memory is encoded in the tube’s diameters of its network-like body. The slime mold’s tubes grow and shrink in diameter in response to the nutrient’s location.

These brain-less organisms do not only possess this remarkable associative memory and problem-solving skills, but also exhibit some form of self-awareness. When it encounters a structure, such as a wall it has to go around, the two arms of the slime mold branch out around the wall and, once they come together touching one another, one of the retracts. This suggests that it knows to be the same unity–that is, it is self-aware of itself as a single organism.

But, after all, are these complicated experiments really necessary to convince us that this uni- or multi-cellular beings possess some form of cognition? When we look at an amoeba, a stentor roeselii, or a paramecium under a microscope or plants in a time-lapse video, what do we see? Dead automatons behaving mechanically? If one looks carefully, one can see that all the behaviors described above were already manifest and evident in the microscopic or time-lapse videos. Is a tiny unicellular creature that swims through a fluid, hunts for its prey, avoids obstacles, has a memory, and can even predict events in advance just a simple machine to which we shouldn’t ascribe at least some form of primitive cognizance, a basal cognition, and eventually even some elementary form of sentience? Is a climbing plant that nervously flatters its tendrils throughout space, analyzes the environment, grows towards support it apparently ‘sees’, and begins to grab for it before even touching it only a machine driven by a chemical reaction?